Manufacturers, particularly those involved with precision press-fit assembly, are very familiar with the following scenario. The customer’s design engineers define a part assembly’s required geometry and performance and leave the “how-to-achieve-it” part up to the supplier. Sound familiar?

The standard response usually involves building very precise tools and fixtures that in reality face constant adjustment in use, mainly due to the unpredictable variations in assembly components. Suppliers do their best to “press and hope” and then “measure and sort.” The scrap and re-work that results are simply tallied up as a cost of doing business.

Such costs can be avoided. Integrating sensors, powerful software and data analysis tools with precision presses brings not only the power to precisely deform metal and perform precision press-fit assembly tasks, but also the ability to gather data and generate unlimited signature curves of the process while it happens. This leads to such possibilities as pressing to a programmable position, to an offset, or to a rate of change. “Press and hope” followed by “sort and toss” gives way to establishing parameters for perfect parts (at times with looser tolerances or less press force necessary than originally thought) and then cloning them with regularity.

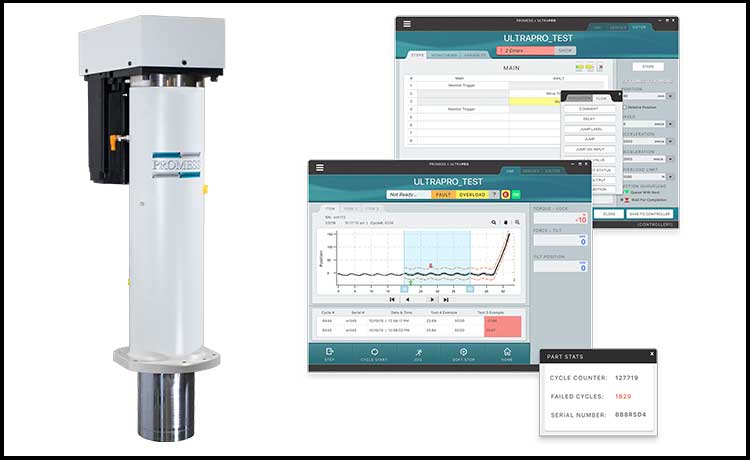

Such a system involves the integration of high level electronics, force and distance sensors, coupled with precision press mechanics and intuitive software. This allows a press to have sense of feel or touch. Signature analysis, unlimited gaging points and integrated programming language with a complete math engine allow for generating signature curves, analyzing data, compensating on the fly, with the utmost confidence that a good part is being made every time. Providing this type of high-precision closed-loop control allows for endless possibilities in many assembly manufacturing applications and gives way to a new breed of ‘intelligent presses’.

Servo presses or EMAP presses along with the newest addition of Rotational Servo presses (REMAPs) already utilize this type of precision control. New thinking, coupled with this type of technology can, will and has solved many manufacturing quality issues that come up in today’s manufacturing environment.

Press-Fit Assembly Application

Millions of steering column hinge mechanisms, for example, must be assembled and pressed relative to how they function. The possibility of testing their function during assembly not only can compensate for component variations, but also offers significant process and cost savings.

For this application, we provided two servo presses designed to operate in conjunction with each other. Servo Press 1 presses and forms the assembly’s rivet/pivot pin while Servo Press 2 actuates the hinge mechanism back and forth. To work properly, both presses must be capable of measuring and controlling force and distance very accurately while being able to communicate with each other and record data.

The amount of force applied to form the rivet/pivot pin in place directly affects how much force is necessary to make the hinge mechanism function. The two Servo Presses work together forming the rivet/pivot pin and exercising the hinge mechanism until the correct ‘exercise force’ is reached. Once the exercise force is reached, Servo Press 2 tell Servo Press 1 to stop. A final exercise motion by Servo Press 2 is completed to ensure the assembly is within the correct ‘exercise force’ tolerance. The data is then stored and the part moves on to the next station, thus assuring a quality functional part has been made. In this case, such a “press to function” method makes good parts every time regardless of variations in the components that make up the steering column hinge mechanism assembly.

Given that there are not only numerous parts that need to be pressed and assembled, but literally thousands more that crank, ratchet, bend, or spin under load, the ideas for gathering and generating press signatures to capture this data really starts expanding.

Adding sensing and data-gathering capabilities to press-fit applications does not have to be a science-project nightmare of myriad custom components. Quite the contrary, establishing intelligent press-fit assembly systems that can monitor and establish upper and lower control limits for pressing, testing, and assembling an infinite number of applications is indeed limited only by the engineer’s imagination.